California’s Second Great Gold Rush

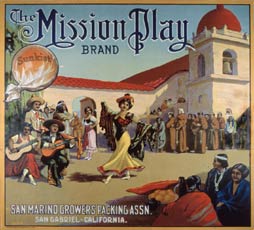

California’s Second Great Gold Rush California’s Second Great Gold RushOur Citrus Heritage by Tom Spellman During the late 1760s, before the United States became a country, the Spanish padres moved north from Mexico into that vast expanse of mountains and valleys known as Alta California. Their intent was to establish a chain of missions, approximately a day’s ride between one another, and settle this new region. One of the first challenges the padres faced was finding a reliable source of produce. They had lots of native game and fowl, and each mission was constructed close to a permanent freshwater source. But native fruits and vegetables were almost non-existent. To survive, immense gardens of vegetables, tree fruits and grapes were planted. The padres brought with them the precious seeds for the Spanish sweet orange—a thin-skinned, seedy fruit similar to the Valencia orange—and a thick-skinned citron-type lemon. Both were completely unknown to the area. The first citrus grove was planted in 1804 at Mission San Gabriel, where fledgling orchards thrived in the warm San Gabriel Valley climate. The trees were vigorous, productive and all welcomed their unique fruits. |

|

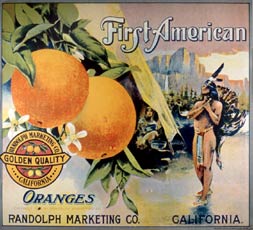

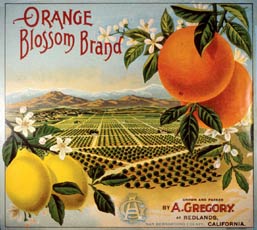

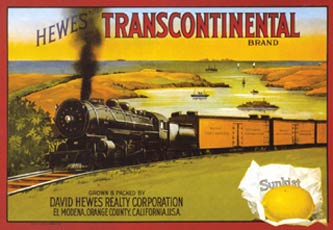

He experienced limited success in these ventures but enjoyed the contrast of the mild Southern California climate to the harsh winters of his Kentucky home, so to stay on, he began a limited farming operation. This was the mid-1830s, and the pueblo at Los Angeles was thriving. Seeing the value in large-scale grape and citrus farming, Wolfskill prepared citrus seeds by visiting the Mission San Gabriel, then in February 1836, he filed a petition with the Mexican government. Within three When the gold rush of 1849 hit, Wolfskill was in full production and took advantage of the new market for his fruit. By ship, he sent his produce up the coast to San Francisco, where miners were willing to pay as much as $1 each for lemons and oranges as they offered the only local prevention for scurvy. Wolfskill worked diligently to improve the quality and yield of his citrus and to combat insect and disease problems. For this effort, Wolfskill is considered the “father of the early citrus industry.” Before he passed away in 1866, Wolfskill had more than 100 acres in production with 70 acres devoted to citrus. The Citrus Boom The second revolutionary event was the first shipment of oranges to the Midwest. With the completion of the transcontinental railroad system, travel time and costs were dramatically reduced, providing an effective new means of shipping produce. This inspired Joseph Wolfskill, William Wolfskill’s son, to make arrangements for the first load of oranges to be shipped from Los Angeles to St. Louis via the recently built Southern Pacific Railroad. Each fruit was individually wrapped in paper and packed into divided wooden boxes, a memorial that later became the standard shipping practice of the citrus industry. The fruit was cooled by ice, which had to be replenished 11 times during the month-long journey. The fruit arrived in good condition and the venture proved hugely profitable. Within 10 years of J. Wolfskill’s first shipment, entire trainloads of citrus were being sent east, and growers were realizing profits of $1,000 to $3,000 per acre. Throughout the decade that followed, citrus production expanded rapidly, and farmland used for citrus grew from fewer than 1,000 acres in 1875 to more than 40,000 acres by 1885. Unfortunately, the swift growth spurt caused a case of overproduction. Growers who were used to pre-selling crops on the tree were now faced with having to “pick and ship” on speculation and hope their crops would sell in the Midwest and Eastern markets. By the spring of 1893, the concern over continuing years of unprofitable business spawned a meeting of 100 prominent growers from all over Southern California out of which the Southern California Fruit Exchange was formed. This growers’ co-op organization was so successful at marketing and distributing that growers from all over the state were eager to join. The exchange formally incorporated itself as the California Fruit Growers Exchange, and by the end of the 1905 season, the exchange represented more than 5,000 growers throughout the state and annual sales of more than $7 million. By 1907, a branch of the organization known as the Fruit Growers Supply Company (which subsequently trademarked the name “Sunkist”) was created to supply most all of the citrus growers’ needs such as fertilizers, labels and irrigation. The exchange went as far as purchasing its own lumber mill in Siskiyou County to produce the wooden shipping crates needed for the citrus industry. Production and profits for Sunkist increased annually and through the next several decades weathered the Great Depression, two world wars and several major freezes. The Modern Trend As part of this legacy, the citrus labels depicted in this article are but a handful of the approximately 10,000 images used during the 75-year period of the wooden The once sprawling orchards of lemons, oranges and grapefruit are now condensed to California’s San Joaquin Valley and isolated portions of Riverside, San Diego, Ventura and Santa Barbara counties. This was a far cry from Watch for the January/February 2003 edition of Garden Compass for information on great new varieties, including the Cara Cara Pink Navel, the Gold Nugget Mandarin, the Pink Lemonade lemon, the Wekiwa tangelo and the *censored*ushu kumquat. Tom Spellman, a well-known California nurseryman, is the Southwest sales manager for Dave Wilson Nursery and president of the Citrus Label Society. |

From Garden Compass • November/December 2002 |

The Wolfskill Influence

The Wolfskill Influence weeks he was granted possession of a ranch on a hillside slope in what is now downtown Los Angeles. This land, adjacent to his home, would become his first farm. After a few years of successful experimenting, Wolfskill had all he needed to pursue farming full time. In 1841, he planted his first 2-acre plot of citrus from seedlings of the Spanish sweet orange obtained from the Mission padres. In a short time, Wolfskill’s farm had increased to 28 acres of planted citrus.

weeks he was granted possession of a ranch on a hillside slope in what is now downtown Los Angeles. This land, adjacent to his home, would become his first farm. After a few years of successful experimenting, Wolfskill had all he needed to pursue farming full time. In 1841, he planted his first 2-acre plot of citrus from seedlings of the Spanish sweet orange obtained from the Mission padres. In a short time, Wolfskill’s farm had increased to 28 acres of planted citrus. During the 1870s, two major events dramatically increased the growth of the California citrus industry. In 1873, the Tibbets family of Riverside, California, received two experimental citrus trees from the National Arboretum in Washington, D.C. These trees had originally been sent to the arboretum by a group of missionaries in Bahia, Brazil. The fruit was large, easy peeling, sweet and seedless, with an inverted navel on the blossom end. The fruit was unlike anything the local citrus farmers had seen before, and by 1875, citrus growers were paying as much as $5 per bud for propagation material from this unusual navel orange. This variety, the Washington navel orange, is still one of the most popular fruits in the world and is considered by many to be the foundation of the California citrus industry. Amazingly, one of the two original parent navel orange trees still survives today in downtown Riverside and is a registered historical landmark.

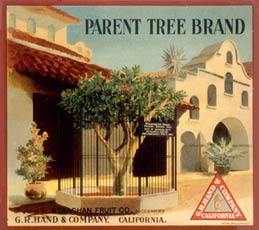

During the 1870s, two major events dramatically increased the growth of the California citrus industry. In 1873, the Tibbets family of Riverside, California, received two experimental citrus trees from the National Arboretum in Washington, D.C. These trees had originally been sent to the arboretum by a group of missionaries in Bahia, Brazil. The fruit was large, easy peeling, sweet and seedless, with an inverted navel on the blossom end. The fruit was unlike anything the local citrus farmers had seen before, and by 1875, citrus growers were paying as much as $5 per bud for propagation material from this unusual navel orange. This variety, the Washington navel orange, is still one of the most popular fruits in the world and is considered by many to be the foundation of the California citrus industry. Amazingly, one of the two original parent navel orange trees still survives today in downtown Riverside and is a registered historical landmark.

Today

Today  shipping box: 1880 through the mid-1950s. Today, these labels are highly prized by collectors and are considered a historical reminder of an industry that is responsible for the founding of many of Southern California’s towns and cities. Towns like Highland, Cucamonga, Upland and San Dimas were once just rail stops for the early citrus industry.

shipping box: 1880 through the mid-1950s. Today, these labels are highly prized by collectors and are considered a historical reminder of an industry that is responsible for the founding of many of Southern California’s towns and cities. Towns like Highland, Cucamonga, Upland and San Dimas were once just rail stops for the early citrus industry. the days when it was said that while driving through Southern California during the 1930s and 1940s, you could smell the orange blossoms for 100 miles.

the days when it was said that while driving through Southern California during the 1930s and 1940s, you could smell the orange blossoms for 100 miles.